Brexit – three and a half year ongoing issue

- European leaders have agreed to extend the deadline to 31 January, 2020.

- Britain wanting to quit EU is driven by various reasons such as threat of their sovereignty, immigration, economic obstacles, and huge national income being given to the EU and so on.

- According to Gartner, the average U.K.-based employee spends about 25minutes daily thinking about Brexit — which amounts to about 2 hours a week

The UK joined the European Union in 1973 (known as European Economic Community back then) which is an economic and political union involving 28 European countries. The 28 member countries agree to open their borders to other EU members, share a common market, and abide by various social and political policies.

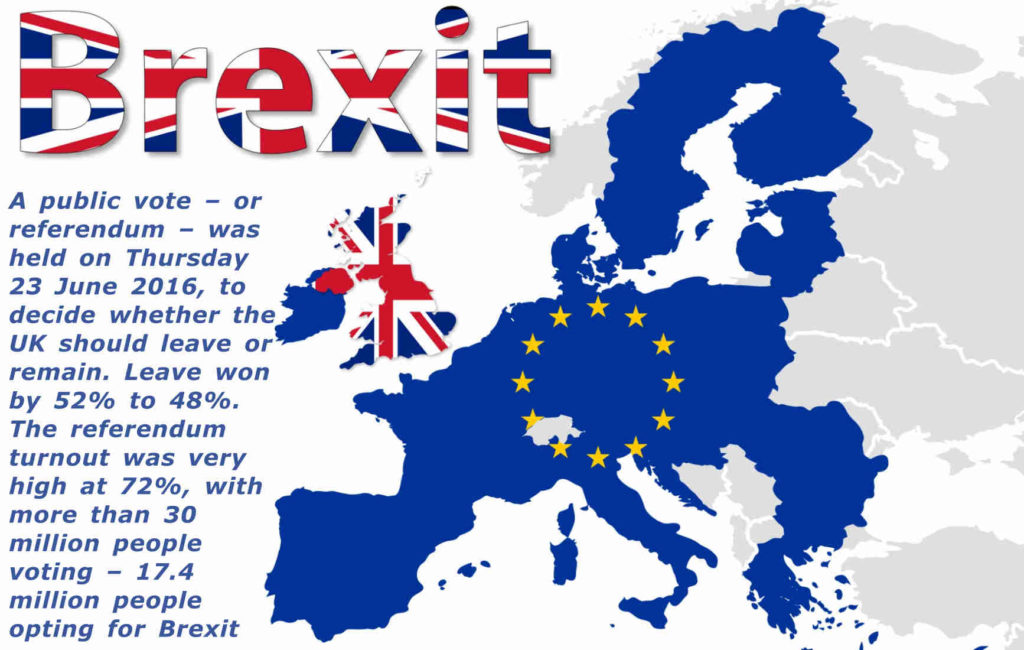

Britain has been haggling over the nation’s withdrawal from the European Union, the process known as Brexit, since the referendum in 2016. Brexit basically is a blend of two words – British and exit, meaning Britain’s split from the European Union, changing its relationship to the bloc on trade, security and migration.

Britain has been debating the pros and cons of membership in a European community of nations almost from the moment the idea was broached. It held its first referendum on membership in what was then called the European Economic Community in 1975, less than three years after it joined, when 67 percent of voters supported staying in the bloc. In 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron promised a national referendum on European Union membership with the idea of settling the question once and for all.

The options it offered were broad and vague — Remain or Leave. A public vote – or referendum – was held on Thursday 23 June 2016, to decide whether the UK should leave or remain. Leave won by 52% to 48%. The referendum turnout was very high at 72%, with more than 30 million people voting – 17.4 million people opting for Brexit.

Just about the only clear decision Parliament has made on Brexit since the 2016 referendum was to give formal notice in 2017 to quit, under Article 50 of the European Union’s Lisbon Treaty, a legal process setting it on a two-year path to departure. That set March 29, 2019, as the formal divorce date. Brexit was originally due to happen on 29 March 2019. That was two years after then Prime Minister Theresa May triggered Article 50 – the formal process to leave – and kicked off negotiations.

When it became clear that Parliament would not accept Mrs. May’s deal by then, the European Union agreed to push the precipice back to April 12. But the new deadline did not yield any more agreement in London, forcing Mrs. May to plead, again, for more time. Under Mrs. May, the deadline was delayed twice after MPs rejected her Brexit deal – eventually pushing it to 31 October, 2019. Mr. Boris Johnson took office in July, and vowed to take Britain out of the bloc by Oct. 31, with or without a deal. But opposition lawmakers and rebels in his own party seized control of the Brexit process, and moved to block a no-deal Brexit and the prime minister’s efforts to hasten an exit. That in turn forced Mr. Johnson to seek an extension and European leaders agreed to extend the deadline by three months, to 31 January, 2020.

On the day of referendum, about 12,369 people, who had finished voting, were questioned and nearly half (49%) of leave voters said the biggest single reason for wanting to leave the European Union was “the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK”. The sense that EU membership took decision making further away from ‘the people’ in favor of domination by regulatory bodies is said to have been a strong motivating factor for leave voters wanting to end or reverse the process of EU influence in the UK. Here, from this data one of the reasons for wanting to leave EU was the threat of their sovereignty.

Also, one third (33%) [of leave voters] said the main reason of leaving was that it would offer the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders. According to The Economist, areas that saw increases of over 200% in foreign-born population between 2001 and 2014 saw a majority of voters back leave in 94% of cases. The Economist concluded that high numbers of migrants don’t bother Britons; high rates of change do. Goodwin and Milazzogo on to explain that the non-British population of Boston in Lincolnshire became 16 times larger between 2005 and 2015, rising from 1,000 to 16,000.With such easy migration policy, it is very logical for UK to be scared of refugees or terrorists as well.

There were some advocates of Brexit who saw leaving the EU as an economic opportunity for Britain. The Office for National Statistics, quoting analysis from the European Commission, states the UK’s actual net average annual contribution to the EU budget, taken from a five-year average from 2014 to 2018, when its annual rebate and public and private sector receipts are excluded, is £7.7 billion(Divided by 52, this equates to £150 million per week). This is definitely not a small amount but is a very big reason for UK to quit EU.

Despite of all these reasons to leave the EU, there are certain things that need to be thought of.The U.K.’s referendum vote to leave the European Union (EU) caught many within and outside the U.K. off guard.We know that Britain is the mixture of various economies. Various international companies have invested in the Britain economy. The singular issue of Brexit has consumed the United Kingdom for two-and-a-half years. The “if”, “how” and “when” of the country’s withdrawal from the European Union, after decades of membership, has understandably dominated news coverage, and sidelined almost every other policy debate.

John-David Lovelock, research vice president at Gartner, noted that business discretionary IT investments, which struggled during the run up to the vote, will suffer in the short term and the effects will spread further than Western Europe.The U.K. employee confidence index dropped 6% in 2019 to 44.6, significantly below the international average of 51.6, according to the 2019 Gartner Global Talent Monitor (GTM). Employees’ perceptions of job availability and quality also declined, contributing to a drop of nearly 8% in active job-seeking behavior among U.K. employees. Only 14% of U.K. employees actively sought a new job in 2019 — 17% less than in the prior quarter and 29% less than the year before.

Now, a question can arise - why Britain wants Brexit?

According to Gartner, the average U.K.-based employee spends about 25minutes daily thinking about Brexit — which amounts to about 2 hours a week. Due to the economic uncertainty surrounding Brexit, a once-optimistic U.K. labor market now seems to be running out of gas,” says Brian Kropp, Distinguished Vice President of Gartner. “As opportunities, rewards and bright business prospects are thought to be fleeting, we may see a global decline in the near future.”